- Home

- Alex MacBeth

The Red Die Page 3

The Red Die Read online

Page 3

‘Ernesto’ entered the casino. Fat, middle-aged white men with pretty African girls drank beer and ate lobster. He walked past them all and took a seat at the bar. “Double whisky, straight,” said the Comandante and the barman didn’t bother asking if he wanted ice. Candles lit up small boulevards leading to a pool in the centre, where a group of younger white men and skimpily-dressed local girls were playing some sort of drinking game. A few solitary rich men played slot machines in a larger room at the back, while a band dressed in butler waistcoats played covers of Stevie Wonder and Lionel Richie songs.

Felisberto knocked back his drink and ordered another. A small man with a personal cohort of security was leaving through the back entrance in the distance. Something about the man seemed familiar. The Comandante could have sworn he’d seen the face somewhere before in another time and in another place. As the figure disappeared out of the faint light in the distance Felisberto realised his mind must be playing tricks with him.

He pulled out his phone and texted his mother to say he wouldn’t be back until the next day. A topless man wearing wet trunks stood beside Felisberto and ordered two bottles of pink champagne. The man’s wet trunks rubbed against Felisberto’s jacket. On another day Felisberto might have had words with this white man but he couldn’t afford to blow his cover over a few drops of water. The man walked off with his ice buckets and Felisberto was at last alone again, even if damp.

“Mind if I join you? You don’t look like you’re waiting for anybody,” said a female voice behind him. Before Felisberto could answer, a tall and slender woman in her early thirties had parked herself beside him. Felisberto didn’t like having his privacy intruded. He tried to say something but the words got stuck in his throat as the woman’s smell caused a chemical reaction in his mind and body. She carried a strong scent of frangipani perfume. The Comandante tried to refrain from breathing in the incantation but the more he resisted, the more intoxicated he became.

“You married?” said the girl, pointing at the engagement ring on Felisberto’s finger. The Comandante tried to focus on the marble on the bar, but all he saw was the reflection of the girl in the red dress: her black mole, the long, curvy hair, the way her legs dangled off the end of the chair but never reached the ground. His wife Adija had always sat the same way. Adija. Since she’d gone, he had practically forgotten what it felt like to flirt with a woman in a bar. The Comandante’s new friend ordered an Amarula and lit a cigarette.

“Bia,” said Felisberto’s new drinking partner, lifting her eyebrows and pouting her lips the way beautiful women do when they expect their audiences to be spellbound. “Ernesto,” lied the Comandante, kissing her hand. They smoked and looked at each other. “You didn’t answer my question,” said Bia.

Felisberto looked down at the ring and twisted it round his finger a few times.

“I think you’re married,” persisted Bia. “Or you’re just the sentimental type.”

Felisberto ordered two more drinks and they watched each other. Bia broke the silence.

“You’re not from here, are you?”

“No, well, not really,” said Felisberto. “I’m a journalist. Just up from Maputo working on a story.”

“Journalist?” Bia’s lips parted in awe and the dress shifted an inch left, giving a faint glimpse of nipple, before readjusting itself to its normal position. “I simply love the media. What is the story?” she asked full of wonder.

Felisberto paused. He hadn’t been in this situation for years. “It’s a story about national security,” said Felisberto taking a long sip on his whiskey. “Unfortunately I can’t discuss the details.”

Half an hour later Felisberto and Bia took a taxi to a local pensão hotel. He made love to Bia against the wall before both collapsed and fell asleep with the sound of rain beating down on the zinc roof. The Comandante dreamt of the oil covered Michelin Man. This time the river in which Felisberto had swam as a child morphed into a snake. The snake choked on a barrel of oil and the river became an offshore rig run by the two Chinese clowns. A giant red die hung above a circular conveyor belt filled with sooted children. Thick leathers made of human skin beat down at intervals as the children jumped and ducked for their lives. Some were thrown off the edge into a cauldron of lava below. The dead man, sitting on the number 1 on the giant die, gave betting odds to skeletons. When Felisberto awoke, Bia had gone and all that remained was the faint scent of frangipani on his sheets. His car keys and wallet were still on the bedside table.

He put on his jeans and trainers and walked downstairs. He was relieved to find his car was still parked a few hundred metres from the bar outside the local district police station. The police station guard looked at Felisberto before stepping forward with his gun. “This is a police car,” said the guard in his late teens, blocking Felisberto’s way. “Not from here,” said Felisberto, waving his badge. The young guard shrivelled back to his post.

Felisberto stepped inside the car and noticed there was a capulana, the wrap-around dress worn by East African women, on the passenger seat below a newspaper where the photo of the dead man and the minister had been. The photo was gone.

Capulanas usually have a proverb in Swahili but this one had a handwritten scribble. Felisberto unfolded the cloth and laid it on his window screen to read the note, evidently addressed to him: “WE ARE WATCHING YOU Comandante,” it said in big bold letters. Felisberto drove home. He texted Dona Paola: I won’t be back for dinner.

Chapter Five

As Felisberto drove past the fields of high grass and straggling moringa approaching the intersection at Namialo, gone were the memories of childhood that had consumed his mind driving the other way. All he could think of now was the capulana. Was it Bia who had put it there? He didn’t even have jurisdiction in Pemba. If the provincial comando in Nampula were to find out what he was doing he could lose his job.

What concerned him most was that somebody in Pemba knew about the dead man. Somebody had been following him. Had he been set up? Were the Chinese engineers after him? A lorry swerved to avoid the Comandante’s Jeep, almost running over a mother and child carrying baskets of manioc on the side of the road. Felisberto pulled up, parked and rubbed his eyes. He drove on a few minutes until the car huffed and puffed then stopped beside the Nampula Wildlife Reserve sign. He was out of petrol. He realised the dial must have been flashing for at least half an hour.

He waved down a motorbike with his police ID and told the driver to guard his car. He found a young boy on the side of the road selling a few old vegetable oil bottles filled with petrol and bought them all.

“Is it diluted?” asked the Comandante.

“Of course not, boss,” said the boy, as if someone had offended his mother.

“Better not be,” muttered Felisberto. He was upset that he would have to top-up the comando’s petrol budget again from his own pocket. The way he saw it, the people who put together the district petrol allowances in Maputo didn’t know anything about solving crimes.

It was 3.47pm when the Comandante finally arrived back in Mossuril to the comando, Mossuril’s new grey and white police station: too late, he realised guiltily, for lunch with his mother and kids. Dona Paola regarded mealtimes with almost religious zeal, sending him lunch or dinner at work in a complicated series of tin cans whenever he failed to go home for the meal. She had made the sacrifice of leaving her comfortable house in Matola, with a major city bustling around it, to live in a mud hut. But she considered her son’s failing to sit down and break bread with them as the worst of his sins. Unable to face his mother’s wrath, Felisberto settled into his office with a tepid Coca-Cola, half a packet of cream crackers and what was left of the day’s supply of putos.

Across the dusty street, the market had hit its afternoon lull. The sellers were sitting in the shade playing cards and smoking. A group of young men were chatting beside a rackety table-football arena, chewing miswak bark to sparkle their teeth for evening encounters. Inside the comando,

João and Amisse were eating cashews and watching Balacobaco, a Brazilian soap. Both tried to outdo each other to free up a hand to salute the Comandante, but Felisberto walked straight past them and into his office.

Why the message in the capulana? ‘We’re watching you Comandante’. Who was watching him? The engineers? It seemed to Felisberto that the most likely scenario was that Bia was working for the engineers and had set him up. She probably took his keys when he was asleep and swapped the capulana for the photo in his car. She’d probably taken a photo of his ID card on her phone too.

A knock on the door brought the Comandante back to the present. “Comandante, Monapo returned the results on the dead man from Quissanga,” said Samora.

“Come in,” replied the Comandante.

“The man was poisoned with strychnine. He would have died within two hours of ingesting it. Raquel from forensics reckons he would have been dead at least an hour before we found him, so between 2:40 and 3:40am,” said Samora, reading from a report and then handing it to Felisberto. The Comandante perused the document.

“Chief Naissone from Immigration sent a fax too,” said Samora. “I gave him my email address, but—”

“Naissone isn’t the type for email,” interrupted Felisberto, proud of his old colleague.

Felisberto walked over to the rusty fax machine and read the note.

“The identity of the man in the photo you requested is John Stokes, a British national resident in Mozambique for the last four years. Last known profession was as a journalist, although we think he also worked as an interpreter.”

“Good to know you’re alive, Matola.”

“Matola?” queried Samora, not able to withhold a snigger. Maria Matola, Mozambique’s multiple gold-medallist in the 400 and 800 metres at the Olympics, was a legend. But she was also a woman.

“I was known for being fast at Special Squad,” said Felisberto casting a glance at his deputy that made clear that the nickname would not be readopted at the comando. “Now that you’re not in zombie mobile zone, maybe I can have your attention for some real police work. We know the identity of the dead man. And we know the identity of two Chinese men who were in the photo with him and—”

“And, Comandante, we know that His Excellency the minister is somehow involved,” interrupted Samora.

“We don’t know that at all,” said Felisberto. “We only know that the dead man was once pictured with Minister Frangopelo. But we certainly do not know that His Excellency the minister…”

The Comandante’s voice tailed off. What if this minister was at the centre of it all? What had they stumbled on that night in Quissanga Bay? If the minister was involved and the shootings in Maputo, the day before, were linked to the dead man in the suit and the Chinese engineers in the green Toyota Land Cruiser, such an alignment of events would not bode well for the Comandante.

Samora could see Felisberto was growing increasingly upset. “What’s up, Comandante?”

Felisberto took a gulp of water and lit a cigarette. He stood by the window smoking, watching the schoolchildren slowly drift home in their white shirts and blue trousers, the bolder and more enterprising of the teenage boys courting the girls in blue skirts. Behind the stone statue of Eduardo Mondlane, modern Mozambique’s founding father, a group of boys played football watched by a clique of girls.

“Comandante?”

Felisberto exhaled in the direction of the Chinese fan, which split the smoke rings into smaller fumes. He turned his head slowly to Samora, the way a father tells his son of a difficult moment in his distant past.

“Did I ever tell you why I left Special Squad?”

Samora shook his head. The Comandante braced himself and began to recount the Palma Affair.

“In 1994, Special Squad was charged with creating a new division for the safeguarding of senior government figures and individuals who it was deemed ‘important to protect in the interests of national security’. I was asked to join and naturally I did. It was a different age back then.”

“A better age?”

“There was a euphoria,” Felisberto continued, hardly acknowledging the interruption. “The war had ended. Apartheid had collapsed. We’d had a successful and free election. I joined what was known in the Squad as ‘the Ministers’ Boys’. Everyone was jealous of us. Every time the Ministry of Interior Affairs ordered a new batch of cars, we’d get first pick. We could search without warrants and arrest without charge.”

“All that to protect national security?”

Felisberto stubbed out his cigarette and laughed at the idealism in Samora’s questions. “We’d been at war. Our ministers were trying to rebuild a State and we had people trying to kill them. The world was watching and for the money to keep trickling in, we had to get it right. So we hustled a few hoodlums to keep the peace.”

“Where did it all go wrong?”

“On the night of August 24th 1995,” began Felisberto, lighting another cigarette. “Naiss and I were driving Palma, then a minister, to a social event. On the way home Palma ordered Naiss, who was driving, to divert towards the port.”

“Why?”

“Naiss asked no questions,” continued Felisberto, his eyes tightening. “Before we knew why, we were parked beside a large container. It was quiet. Then Palma ordered Naiss and me to board a battered old fish trawler with him.” Felisberto remembered the rusty Vasco da Gama. He ashed his cigarette and paused before continuing.

“Naiss and I felt strange that a government minister insisted on walking behind us. I mean, we were his bodyguards: it was against all the protocols. Normally, one of us would have walked behind him, one of us in front.”

“I get it, but what—”

“The old wooden boards creaked as we made our way off land and onto the boat,” continued Felisberto. “When we reached the deck above, we weren’t alone. Seven men were waiting for us with knives. Then Palma played his cards. Either we sold drugs for him or he would leave us to settle old scores with the gang on the boat.”

“Why didn’t you refuse?”

“We weren’t afraid of the knives, we took down men like them night after night. But Palma sealed the deal himself smashing his head against a pole.”

“Huh?”

“He said he’d denounce us for violent conduct if we refused,” continued the Comandante. “Palma could spin any situation as he wanted.”

Felisberto stared into the glass of water on his desk. Every ripple dragged him back to the sound of the waves and the Vasco da Gama in Maputo back in ‘95.

“So what did you do?”

“We told Palma we’d do whatever he wanted us to do. It bought us some time to think. Neither of us had a viable get out plan though by the time we were due to make our first drop for him. Naiss tried a witchdoctor but a few spread chicken bones later we were still stuck between a minister and several bags of heroine.” Felisberto lit another cigarette.

“Palma wanted us to pick up from him on Thursdays,” recalled Felisberto. “We arranged to meet him at his residence, where he gave us a carpetbag full of drugs for what should have been the first drop. We were supposed to drop him off at an Embassy dinner and then deliver the bag to an address at the port. It was meant for export, I think.” Felisberto paused and pulled another Gran Turismo cigarette from a pack on the desk. He tapped it on the table for a while before lighting it.

“So what did you do?” Samora asked. Felisberto shrugged. “Nothing. We didn’t do a thing. Fate intervened in the end,” said the Comandante chuckling. “Of course, my partner Naiss said it was all his witchdoctor’s doing and paid the gajo nearly two months’ salary for his supposed magic.” Felisberto inhaled and smiled, remembering the sweet release when the minister had keeled over in the back of their government-issue car and sunk into a deep coma. “He’d been acting so strangely ever since we first met him that it didn’t occur to us that he had cerebral malaria.”

Felisberto reached into his bag of putos and ate the last on

e.

“What happened next?”

“Palma was rushed to the Military Hospital and then evacuated by helicopter over the border,” said Felisberto lighting another cigarette. “He spent the next year in hospital in a coma while in his wake things got serious. In his confused state, Palma had left a trail of heroin so long that if the Taliban had known they might have been tempted to leave Afghanistan and occupy his home.”

“And?”

“They found a powder trail that took them right into Naiss’ and my car. Anyone who had anything to do with His Excellency Minister Palma was arrested while he just languished between life and death in his five-star coma.”

“What happened next, chefè?”

Felisberto suddenly regretted having been so confiding in his deputy.

“What happened to you?”

“We went to court.”

“Was it a big case?”

“It was the first time they had put two senior officers on trial. I was facing multiple charges of possession of illicit substances with intent to distribute and half a dozen charges I forget. The first day of the trial there were twenty cameras at the court. I didn’t even realise Maputo had that many photojournalists until they were snapping my mug shot for their paper.”

Samora gave his phone to Felisberto.

“I believe that is said mug shot, boss,” said Samora with evident pride in his investigative work. Felisberto flicked through the pictures of himself from the trial and wondered what had happened to all those years. In the photos he was slim. He was dressed in a new suit and wearing shiny tapering shoes. He remembered how uncomfortable they’d been but how he had prized them all the same for their light touch on dance floors. He shrugged and looked down at the battered boots he had on now and tickled the hair ends on his unkempt beard. In the photo was a clean-shaven officer with a twinkle in his eye. Even if it was just an image, in some ways it had more life than he did at 45.

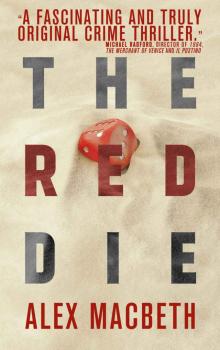

The Red Die

The Red Die